By Rabbi Shaul Marshall Praver

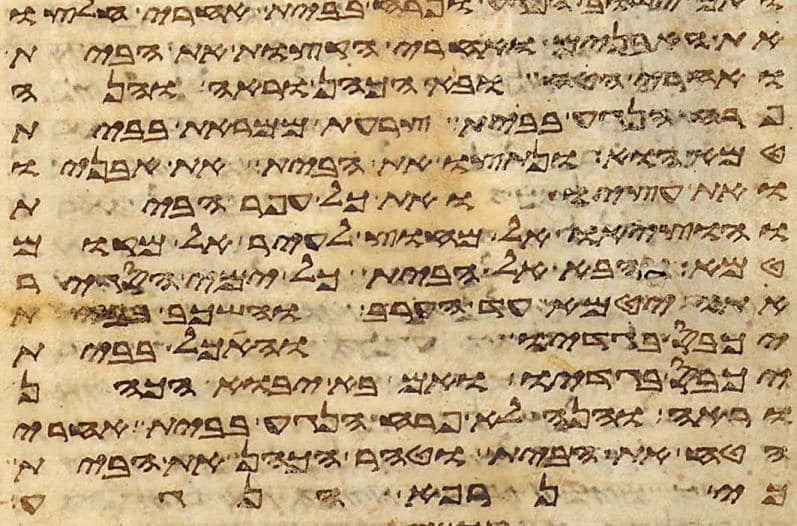

The first written language is believed to be Sumerian language, which originated in the ancient region of Sumer in Mesopotamia around 4000 BCE. The Sumerians developed a system of writing known as cuneiform, which involved pressing a stylus into clay tablets to create wedge-shaped impressions. This system was used to record various aspects of life, including religious rituals, trade transactions, and administrative affairs. While other cultures such as the ancient Egyptians and Chinese also developed writing systems around the same period, the Sumerian cuneiform is considered the world’s first known writing system.

The world’s first written language fulfill the need of memorializing daily transaction money in, money out, assets and debts; real estate and/or livestock trades. From there it expanded.

The Cuneiform writing system was also used for notating other languages of the Middle East including: Akkadian, Elamite, Hittite and Old Persian. Akkadian: a Semitic language that was spoken in ancient Mesopotamia, Akkadian was written in cuneiform script and became the dominant language of communication and literature in the region during the 2nd and 1st millennium BCE. Elamite was an agglutinative language that was spoken in the ancient Elamite kingdom, which was located in modern-day southwestern Iran. Elamite texts written in cuneiform script have been found in archaeological sites across Mesopotamia and date back to the 3rd millennium BCE. The Hittite language was spoken by the Hittite empire, which was based in Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) during the 2nd millennium BCE. Hittite texts written in cuneiform script have been found in several ancient sites and provide important insights into the history and mythology of the empire. Old Persian was an Indo-Iranian language that was spoken by the Achaemenid Empire, which was based in Iran from the 6th to the 4th century BCE. Cuneiform inscriptions in Old Persian have been found on several monumental sites, including the famous Behistun inscription.

Sumerian cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphs were two of the earliest systems of writing in the ancient world, and they emerged at roughly the same time in different regions.

Egyptian hieroglyphs first appeared in Egypt around 3,400 BCE. There is evidence supporting the belief that Sumerians and Egyptians had contact with each other, and it is likely that they influenced each other’s writing systems to some extent. It is possible that the early Egyptians may have borrowed the concept of writing from the Sumerians, although the sophisticated hieroglyphic script that they developed was unique to Egypt and evolved independently.

Some scholars have suggested that there may have been cross-cultural exchange between the two civilizations, as evidenced by the presence of Sumerian loanwords in Egyptian and the use of Egyptian materials and goods in Mesopotamia. However, the extent of this exchange and its impact on the development of the two writing systems is still unknown.

Most people are more familiar with the Egyptian hieroglyphs for their striking beauty and imagery. The fact that the Egyptians wrote on papyrus and the Sumerians wrote on stone or clay tablets may have contributed to the survival of more Egyptian records. Papyrus paper was more fragile than stone or clay, and more prone to decay. On the other hand, papyrus was also relatively inexpensive and plentiful in Egypt, which made it easier for scribes to produce a greater quantity of written records.

Whereas, the Sumerians used clay tablets to create their inscriptions, which were more durable than papyrus but also more difficult and time-consuming to produce. Unfortunately Mesopotamia was more prone to natural disasters such as floods and earthquakes, which could have led to the destruction of many of the clay tablets. Despite these factors, many Sumerian inscriptions and texts have been discovered and preserved, but there are fewer Sumerian relics than Egyptian records. Egyptian hieroglyphs are mystical and artistic expressions. Whereas, cuneiform is not of beautiful form, but is favored for its ability to be written quickly and has phonetic expressions needed for the bustling commerce of Mesopotamian life.

The Sumerian economy was primarily based on agriculture and trade. The fertile land between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, known as Mesopotamia, “between the rivers,” was home to the Sumerians, who developed an advanced system of irrigation and farming. They built extensive canal systems that allowed them to manage water flow and cultivate crops year-round and were able to grow a variety of crops, including barley, wheat, and date palms.

The Sumerians also engaged in long-distance trade, using the rivers as transportation routes to exchange goods with neighboring regions. They traded textiles, metals, and luxury items, such as precious stones and exotic woods, with regions as far away as the Indus Valley and the Persian Gulf. They also developed a system of weights and measures, which facilitated trade and commerce.

Another important aspect of the Sumerian economy was the development of complex systems of labor and production. Since agriculture was the primary source of wealth, the Sumerians developed a system of land ownership and distribution that allowed for the allocation of resources and the generation of wealth. The emergence of cities and urban centers allowed for the development of specialized crafts and the rise of a merchant class, which facilitated the exchange of goods and services. Overall, the Sumerian economy was characterized by a combination of agriculture, trade, and commercial activity, which supported the development of urban centers, specialized labor, and social hierarchies. While the Sumerians did not have a modern market economy, their economic practices and infrastructure laid the foundation for future economic systems and continue to influence modern economies.

Biblical Abraham is traditionally believed to have been from Ur Kasdim by secular scholars and is explicitly described as such in the biblical narrative. Ur was a city that was located in ancient Mesopotamia and is identified with the archaeological site of Tell el-Muqayyar in modern-day Iraq.

Genesis 11:31: “Terah (Abram’s father) took his son Abram, his grandson Lot son of Haran, (Abram’s brother) and his daughter-in-law Sarai, the wife of his son Abram, and together they set out from Ur of the Chaldeans to go to Canaan. But when they got as far as Harran, they settled there.” After some time and after their father Terach died, Abram set forth to Canaan with his family. “He took his wife Sarai, his nephew Lot, all the possessions they had accumulated and the people they had acquired in Harran, and they set out for the land of Canaan, and they arrived there.” (Genesis 12:5)

Abraham is also referred to as an “Amorite” or “Amamean” (depending on the translation), which is a term used in the Bible to describe a group of semi-nomadic people who lived in ancient Syria and Mesopotamia during the 2nd millennium BCE. The Amorites appear in the Bible as a group of people who captured and settled in various parts of the Near East, including Canaan (the biblical land of Israel and Palestine). The Amorite culture is often referred to as the Old Babylonian culture and generally covers the period from around 2000 BCE to 1600 BCE. The Amorites were a semi-nomadic people who migrated from the Syrian and Arabian deserts to the northern regions of Mesopotamia. They gradually settled in the cities and communities of that region and interacted with the earlier Sumerian culture that had developed there.

Compared to the Sumerian culture, the Amorites were generally more militaristic and patriarchal in nature. Their cultural and social values reflected a more hierarchical and stratified society than the Sumerians, with a greater emphasis on kingship rather than city-states ruled by competing elites. Amorite society was also marked by an expansion of trade and commerce, with a growing emphasis on merchants and mercantile activity.

The Amorites adopted many elements of Sumerian culture, such as their writing system (cuneiform), religion (polytheistic with a pantheon of deities), and agricultural practices, including the development of sophisticated irrigation systems. However, they also introduced new customs, such as the use of chariots in warfare, and introduced new forms of art and architecture that reflected their own cultural traditions. We see Abram referred to as a wanderer which comports with the traveling Aramean merchants. “My father was a wandering Aramean, and he went down into Egypt with a few people and lived there and became a great nation, powerful and numerous.” (Deuteronomy 26:5)

Abram as a “wandering Aramean” recognizes his nomadic nature as he traveled from Ur to Harran to Canaan, Egypt and back again to Canaan. It also emphasizes the fact that he was a stranger and a sojourner in the land.

Abram is eventually called a Hebrew in Genesis 14:13. “And one who had escaped came and told Abram the Hebrew, who was living by the oaks of Mamre the Amorite, brother of Eshcol and of Aner. These were allies of Abram.”

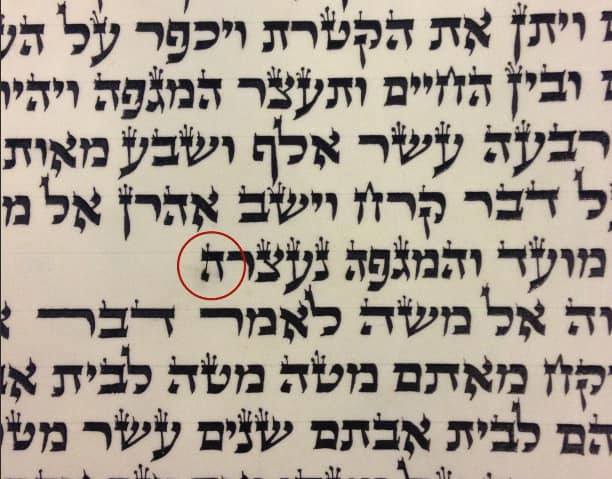

Here, the word “Hebrew” is used to describe Abram’s unique ethnic background and the beginning of Hebrew as a cultural identity. The exact origins of the Hebrew language are still debated among scholars, but many believe that it evolved from the Canaanite language, which was spoken in ancient Canaan, where Abraham and his descendants settled.

Canaan was a region along the eastern coast of the Mediterranean, which encompasses modern-day Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, and parts of Syria and Jordan. Due to its strategic location, the land was a cultural crossroads, with influences from various civilizations such as Egypt, Babylon, and Persia.

The Canaanite language was a complex language with distinctive phonetic and grammatical features, a consonantal writing system, and an extensive vocabulary. The Hebrew language, which evolved over time, inherited some of these features and vocabulary from the Canaanite language. There are several theories as to how Hebrew developed from Canaanite. One theory suggests that Hebrew evolved from the dialects spoken by the Israelites as they migrated from Canaan to Egypt and back. As they were exposed to Egyptian words and grammar, their native language underwent a transformation.

Another theory posits that Hebrew evolved gradually from Canaanite, as the Israelite tribes settled in Canaan and adopted Canaanite customs and language. As they developed their own distinct culture religion and identity, their language also changed, with the introduction of new words and grammatical forms.

Scholars also point to the impact of religious and cultural changes on the development of the Hebrew language. As the Israelites made contact with other civilizations, their religious beliefs and practices evolved, which led to the introduction of new concepts and religious terminology into the Hebrew language.

Aramaic had a considerable influence on the formation of Hebrew. Aramaic is a Semitic language that was spoken throughout the Near East, including in the lands adjacent to Israel, from the 8th century BCE onwards. Aramaic quickly became the lingua franca of the eastern Mediterranean and was widely used in trade, commerce, and diplomacy.

As a result of contact and interaction with Aramaic-speaking peoples, Hebrew borrowed many words, phrases, and grammatical structures from Aramaic. For example, Aramaic influence can be seen in the use of Aramaic loanwords in the Hebrew Bible, such as “golgotha” (meaning “skull”), “shibboleth” (meaning “ear of corn”), and “kippah” (meaning “head covering”).

Aramaic also influenced the development of Hebrew grammar and syntax. For example, Aramaic word order and sentence structure influenced the use of Hebrew word order, which became more flexible. Aramaic also introduced the use of the definite article (“the”) in Hebrew, which had not been used before. Another example is the formation of nouns in Hebrew, which was influenced by Aramaic.

Despite these influences, Hebrew remained a distinct language with its own unique characteristics. The use of Aramaic did not replace Hebrew but rather enriched and expanded its vocabulary and grammatical structures. Aramaic had a significant influence on the formation of Hebrew, particularly during the time of the Babylonian exile when Hebrew speakers were in close contact with Aramaic speakers. However, Hebrew remained a distinct language and absorbed Aramaic influence without losing its unique identity.

During Abraham’s time, the dominant language in the region was likely Sumerian, which was the language of the ancient Sumerians, one of the earliest civilizations in Mesopotamia. However, Sumerian was not long-lasting in its dominant position and was eventually replaced by Akkadian, a Semitic language that was widely spoken throughout the Near East.

It is possible that Abraham, being from Ur, may have spoken a dialect of Akkadian called Old Babylonian as well. This language was spoken in southern Mesopotamia during the time of Abraham and was the administrative language of the region. Moreover, as a merchant and traveler, Abraham would have been exposed to various languages and dialects of the time, including Aramaic, which was becoming increasingly common in the Near East. Aramaic became a dominant language in the region later, after the time of Abraham.

Therefore, it is likely that Abraham spoke a variety of languages, including Sumerian, Akkadian, Canaanite, Aramaic and a little Egyptian.

Leave a comment